Street Art has its roots in the American artistic revolution of the late 70s. Closely linked to graffiti, the origins of this discipline mix with a dark part of contemporary social history, which is connected to the creators’ need for reaffirming their identity, their uniqueness and their sense of belonging. It is not surprising that the first tags represented a battle cry against the pre-established system, class differences, inequalities between collectives… a way to express the discontent of the marginalised, the song of the oppressed materialised with spray in public places.

We hardly remember today “TAKI183”, the first New York tagger who marked an era by spreading his signature throughout the city in the late 60s. And, of course, behind this name was Dimitrios, a Greek immigrant living on 183rd Street, the most marginal part of Manhattan. This initiative had such an impact that the New York Times dedicated to him a reference article in 1971, giving this way an entity to a movement unstoppable. It was not surprising that urban art had its origins in this paradigmatic city of contemporary awakening. A melting pot of cultures with 8 million people united by a feeling of hope that clashed frontally with the reality of the moment. If America was the nation of great dreams, the country of opportunities offered a panorama full of contradictions in which there was still racial segregation, strong gentrification and an inherent mistrust towards the immigrant with aspirations. How were those with no voice going to respond to this situation?

This initiative had such an impact that the New York Times dedicated to him a reference article in 1971, giving this way an entity to a movement unstoppable. It was not surprising that urban art had its origins in this paradigmatic city of contemporary awakening. A melting pot of cultures with 8 million people united by a feeling of hope that clashed frontally with the reality of the moment. If America was the nation of great dreams, the country of opportunities offered a panorama full of contradictions in which there was still racial segregation, strong gentrification and an inherent mistrust towards the immigrant with aspirations. How were those with no voice going to respond to this situation?

The quality leap in these forms of expression came with the evolution of the tag itself. The need for outstanding became different among the artists themselves, and this led to a tense and creative rivalry between spray-masters who were no longer satisfied with just writing their name on the walls. No. Now it was about encompassing and attracting, conquering, being remembered, making the difference, having a genuine presence, about transcending. With this purpose in mind, the works transformed into a display of style and inspiration that turned the urban elements into an immense canvas to invade, with a clear claim factor. And the bigger, more visible and riskier the intervention, the greater the challenge and recognition.

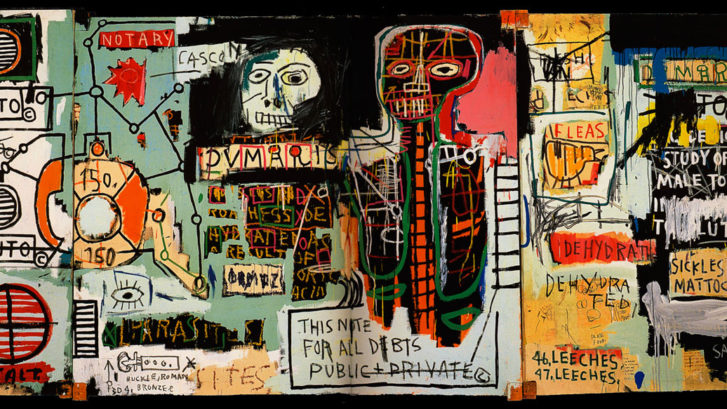

This was the ideal breeding ground for misplaced characters such as Basquiat, who used this language to channel his essentialist disagreement. Acting in the heart of New York’s Soho, the neighbourhood of the galleries, Basquiat and his partner Al Díaz signed their works as “SAMO”, an irreverent “SAMe Old shit” with which they condensed a genuine urban and mural poetry. The essential restlessness of this artist led him to explore the plasticity of his works within Abstract Expressionism but without abandoning the streets. The influence of De Kooning, Franz Kline and Pollock, of Art Brut, of popular culture and his own Puerto Rican and Haitian roots is evident in a pictorial evolution that did not go unnoticed. He finally made the leap to the gallery with the exhibition “Times Square Show” opened in 1980 in an abandoned warehouse in the Bronx, a collective exhibition that was the first official acknowledge in the art market of graffiti and street art, so far outside the mainstream.

A giant step in recognition of urban art occurred when academy artists took the walls. This is the case of another creator who set trends, Blek le Rat, a Parisian painter who began his career after passing through the Fine Arts and Architecture schools and who took over the city walls since 1980. Although he started his career in the company of other school colleagues finally decided to continue on his own, at which time he adopted this name, inspired by the Italian band designed band Blek le Roc. In 1992 he was convicted of vandalism and damage to property, what led him to change his technique and make his interventions painting first on posters that he glued on the wall. Surprisingly, this conviction was not a break down in his career but an exercise of ingenuity to keep on conquering the streets. It was the inception of the “stencil”, the beginning of a whole creative trend that allowed artists to approach more refined techniques and styles, with previous work of study hidden in the eyes of everyone, meditated and thoughtful far away from pure vandalism and random impulse still assigned to this group of artists. As Blek le Rat himself explains: “My stencils are a present, introducing people to the world of art, loaded with a political message. This movement is the democratisation of art: if the people cannot come to the gallery, we bring the gallery to the people!”

A giant step in recognition of urban art occurred when academy artists took the walls. This is the case of another creator who set trends, Blek le Rat, a Parisian painter who began his career after passing through the Fine Arts and Architecture schools and who took over the city walls since 1980. Although he started his career in the company of other school colleagues finally decided to continue on his own, at which time he adopted this name, inspired by the Italian band designed band Blek le Roc. In 1992 he was convicted of vandalism and damage to property, what led him to change his technique and make his interventions painting first on posters that he glued on the wall. Surprisingly, this conviction was not a break down in his career but an exercise of ingenuity to keep on conquering the streets. It was the inception of the “stencil”, the beginning of a whole creative trend that allowed artists to approach more refined techniques and styles, with previous work of study hidden in the eyes of everyone, meditated and thoughtful far away from pure vandalism and random impulse still assigned to this group of artists. As Blek le Rat himself explains: “My stencils are a present, introducing people to the world of art, loaded with a political message. This movement is the democratisation of art: if the people cannot come to the gallery, we bring the gallery to the people!”

The impact of this artist is undoubted and his international projection, difficult to quantify. From very early on, he knew how to merge his creative career between the urban space and the gallery sector, mainly in Paris, but also in the rest of the world. His works are found in all the major western cities, and his influence is undeniable. Banksy himself, perhaps the first great urban artist whose fame overtakes the risky frontiers of this small area of creation, has acknowledged that “Every time I think I’ve painted something slightly original, I find out that Blek le Rat has done it as well, only 20 years earlier.” Banksy is also one of the greats. Perhaps his popularity is primarily due to the message of his works, far from being a mere manifestation that combines aesthetics and defiance of authority, though also so. His stencils in the wall of Gaza, the open criticism of the capitalist system, his political discourtesy and his censorship of social hypocrisy represent a collective clamour with which many identify and have seeped deeply, now that there is a real generational leap in the approach to art. It doesn’t matter whether it is painted on a wall or on canvas. Expressions acquire an absolute, intangible, eternal value, and this has changed the way in which society and cities embrace the already consecrated urban art.

Although Urban Art is now what it has always been: the open expression of a collective feeling to put into question the reality, the lack of honesty, the double morality turned into an artistic manifestation that does not fear public exposure. But at the same time, street art has mostly overcome the reductionist approach as a mechanism of fundamentally critical expression and has been transformed, in many occasions, into a tool of social cohesion, into a shared language that puts together groups and communities around a site. Today we find this double slope of urban art to which the demand of the cities themselves has contributed to a great extent. The interventions in depressed neighbourhoods, in ruined buildings, in devastated areas are a bet for the power of art and its potential for change. This progression and acceptance of street art today allows us to find works in unlikely environments, where we would never believe to see them. It is an unstoppable phenomenon. The community does not satisfy with a cement wall that is raw and inert; it wants to identify itself with what is on display, to participate in those manifestations that back in recent history emerged as the marginal and subversive channel of expression.

A brief review of the birth and evolution of street art shows that the public became used to appreciate this art-expression. And just as this discipline found its origin in the streets, today it moves bi-directionally, between the galleries and the walls of the city. Gone is the censorship, persecution or prohibition. In fact, this type of expression involves a halo of mystery and admiration for artists who gather the courage to face adverse situations to complete their projects. Fortunately, urban art has settled entirely in the market, and many works are made today by order, while many artists combine their mural works with others in more commercial formats, with increasing demand.

Author: Marta Suárez-Mansilla Author: Marta Suárez-Mansilla

Lawyer specialised in cultural law. With extensive experience in the field of Contemporary Art and Project Management, my activity now focuses on approaching the legal issues surrounding this field of work. |

|

© Marta Suárez-Mansilla |